Can the Healthcare System Change Its Spots?

Kim BellardJust a few years ago, things were looking up for the American health care system. We were going to start finding better ways to pay for care: call it pay-for-performance (P4P), value-based purchasing (VBP), or similar terms. We were going to nudge -- or, rather, push -- providers into more clinically integrated systems (e.g., ACOs) to help improve outcomes and to control costs. And, of course, with wider use of electronic health records (EHR), we'd be able to better coordinate care and make decisions based on actual data. It all sounded very promising.

Kim BellardJust a few years ago, things were looking up for the American health care system. We were going to start finding better ways to pay for care: call it pay-for-performance (P4P), value-based purchasing (VBP), or similar terms. We were going to nudge -- or, rather, push -- providers into more clinically integrated systems (e.g., ACOs) to help improve outcomes and to control costs. And, of course, with wider use of electronic health records (EHR), we'd be able to better coordinate care and make decisions based on actual data. It all sounded very promising.

Now, though -- what's that old expression about the leopard not being able to change its spots?

Let's start with EHRs, As Dave Lareau of Medicomp Systems told Healthcare IT News, "the concrete has already been poured." For better or for worse, we've got the widespread diffusion of EHRs that we were hoping for. Unfortunately, it seems more for worse.

Mr. Lareau further noted that "their main purpose was for reimbursement -- to get it over to billing." Jon Melling, of Pivot Point Consulting agreed: "As we move to value-based reimbursement, we have a variety of venues to select, including value-based care and fee-for-value, which are incompatible in the system."

Oh, yes, about those new payment mechanisms.

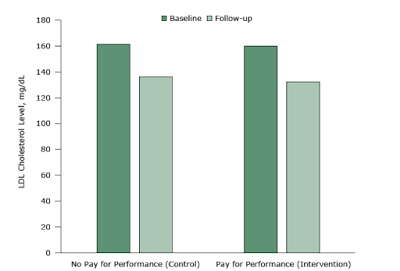

Harvard's Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, says that: "the evidence on P4P in general is largely mixed, and the evidence on Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP), the national hospital P4P program, is discouraging."

According to Dr. Jha, VBP has had no positive effect on either mortality or patient experience, and this should come as no surprise. He'd noted several years ago that successful P4P programs must have three design features:

- incentives large enough to "motivate" investments in improving patient care;

- focus on a small number of high-value measures to drive practice changes;

- a simple design that people can know how they are doing.

Not exactly what we were hoping for.

Like Dr. Jha, Dr. Soumerai and Dr. Koppel aren't entirely discouraged, having faith that providers simply want concrete information -- based on better research about the reasons for poor performance -- that will help improve care. They cite the ever-quotable Uwe Reinardt:

The idea that everyone’s professionalism and everyone’s good will has to be bought with tips is bizarre.

I don't think I've heard P4P ever called "tips" before, but that's not far wrong.

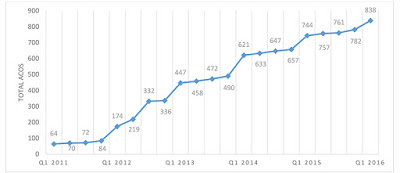

Then there are ACOs. Their number has skyrocketed since the passage of ACA, with there being close to 1,000 nationwide. Whether they've been effective in controlling costs or improving quality is less clear; at best the jury is still out, at worst the answer has been no. What we have seen, though, is that provider consolidation has been on a spree in recent years, with no end in sight. The argument for it is that such consolidation is necessary for the kind of clinical integration that ACOs and P4P require. This is despite the fact that such consolidation has not delivered lower costs or better quality; if anything, costs have increased with it.

What we have seen, though, is that provider consolidation has been on a spree in recent years, with no end in sight. The argument for it is that such consolidation is necessary for the kind of clinical integration that ACOs and P4P require. This is despite the fact that such consolidation has not delivered lower costs or better quality; if anything, costs have increased with it.

As it turns out, though, the consolidation bears little relationship to ACO penetration or physician participation in them, according to research by Neprash et. alia. The post-ACA consolidation simply continues previous trends, although it may now be "defensive consolidation in response to new payment models."

Which, it would seem, may not really work anyway.

So, it would seem, our health care system can't quite seem to change its spots. It's taken every reform we've thrown at it -- every new delivery approach, payment mechanism, regulatory oversight, new competitors -- and come out virtually unscathed. Costs keep going up, unnecessary care continues to be delivered, and thousands of lives are damaged or lost that didn't need to be.

You can't blame the health system, or the people in it. For the most part, everyone in it is just doing what they think is their job. It's not going to change, not on its own. Why would it?

Maybe it is us who have to change our spots.

| Can the Healthcare System Change Its Spots? was authored by Kim Bellard and first published in his blog, From a Different Perspective.... It is reprinted by Open Health News with permission from the author. The original post can be found here. |

- Tags:

- Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

- Ashish Jha

- care coordination

- Dave Lareau

- electronic health records (EHRs)

- fee-for-value

- Jon Melling

- Kim Bellard

- Medicomp Systems

- mobile tracking devices

- national hospital P4P program

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)

- pay-for-performance (P4P)

- Pivot Point Consulting

- quality measurements

- Ross Koppel

- Stephen B. Soumearai

- value-based care

- Value-Based Purchasing (VBP)

- Wearables

- Login to post comments