Is the US Healthcare System Suffering from the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

Kim BellardPsychologist David Dunning, originator of the eponymous Dunning-Kruger effect, recently gave an interview to Vox's Brian Resnick. For those of you not familiar with the Dunning-Kruger effect, it refers to the cognitive bias that leads people to overestimate their knowledge or expertise. More importantly, those with low knowledge/ability are most likely to overestimate it.

Kim BellardPsychologist David Dunning, originator of the eponymous Dunning-Kruger effect, recently gave an interview to Vox's Brian Resnick. For those of you not familiar with the Dunning-Kruger effect, it refers to the cognitive bias that leads people to overestimate their knowledge or expertise. More importantly, those with low knowledge/ability are most likely to overestimate it.

Does this make anyone else think of the U.S. healthcare system? Professor Dunning proposed the effect in 1999, in a paper in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, along with then-graduate student Justin Kruger. Since then, it has become widely known and broadly applied (not always accurately, as Dr. Dunning explains in the interview).

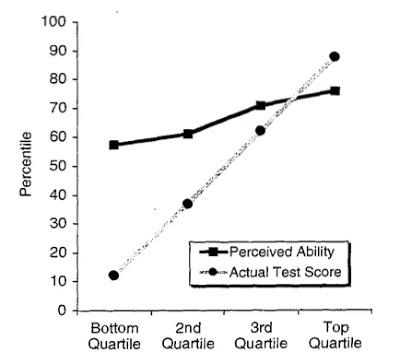

Their paper had a chart that summarized their findings (see below).

Dr. Dunning believes that we tend to think that this effect only applies to others, or only to "stupid people," when, in fact, it is something that impacts each of us As Dr. Dunning told Mr. Resnick, "The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don't know you're a member of the Dunning-Kruger club. People miss that."

Or, as Dr. Dunning characterized it in a 2014 Pacific Standard article, "We are all confident idiots."

So, how does this relate to our healthcare system?

We brag about our excellent care, our great hospitals and doctors, and all those healthcare jobs powering local economies. Yet we have by far the most expensive healthcare system in the world, which is expensive not because it delivers better care or to more of its population than health systems in other countries, but because it feels it is justified in charging much higher prices. Our actual outcomes, quality of care, and equity are all woefully mediocre on a number of measures.

Credit - Dunning-Kruger, Journal of Personality and Social PsychologyHow many of you live in an area that has at least one hospital system claiming to be one of the "best" hospitals in the country? I've lived a lot of places, and each of them had one or more hospitals making that claim. Your local hospital(s) may as well. I hate to break it to you, but, in most cases, that claim is not likely to be true.

Credit - Dunning-Kruger, Journal of Personality and Social PsychologyHow many of you live in an area that has at least one hospital system claiming to be one of the "best" hospitals in the country? I've lived a lot of places, and each of them had one or more hospitals making that claim. Your local hospital(s) may as well. I hate to break it to you, but, in most cases, that claim is not likely to be true.

Similarly, how many of us like to believe that our doctors are "the best"? Perhaps they even have "best doctors" plaques in their offices to support this claim. Again, it's possible that they are, but, in most cases, those beliefs are not likely to be true.

Statistically speaking, most of us receive average care, and some of us receive sub-standard care. We don't live in Lake Wobegon. We can't all be getting the best care, or even above-average care.

Just look at how few hospitals earn high ratings from The Leapfrog Group. Look at nationally or even internationally known hospitals like UNC Children's or Houston Methodist, both of which had embarrassing revelations about the quality of some of their programs uncovered by investigative journalism. Look at how even problem doctors often evade our vaunted medical licensing system.

They all probably thought they were much more capable than they were.

In the Vox interview, Dr. Dunning referred to a 2018 paper he co-authored, which found that beginners don't start out displaying the Dunning-Kruger effect, but often soon manifest it:

Although beginners did not start out overconfident in their judgments, they rapidly surged to a "beginner's bubble" of overconfidence."...Hence, when it comes to overconfident judgment, a little learning does appear to be a dangerous thing.

I think about how uncertain medical school students turn into nervous residents and ultimately become the uber-confident physicians we're used to. Dr. Dunning discussed how we need to do better distinguish facts and opinions, and be more willing to admit "I don't know." How often does your physician admit they don't know something -- and would that give you more, or less, confidence in them if they did?

In The Atlantic, Olga Khazan reported on a new study that suggests that, despite all their supposed superior knowledge, doctors don't really make better patients than the rest of us. They get C-sections about as often, and about as unnecessarily as we do, they get about the same amount of unnecessary/low value tests, they're not better at taking needed prescriptions.

As Michael Frakes, one of the authors told Ms. Khazan, the doctors "went through internships, residencies, fellowships. They're super informed. And even then, they're not doing that much better." Professor Frakes speculated that even physicians tended to be "super deferential" to their own physicians, despite their own training and experience. They're underestimating their own knowledge, and their doctors may be overestimating theirs. A new meta-study found almost 400 "medical reversals" -- common tests or procedures that are not supported by research data. As one of the co-authors told The New York Times: "You come away with a sense of humility. Very smart and well-intentioned people came to practice these things for many, many years. But they were wrong."

It is widely accepted that as much as a third of our healthcare services are unnecessary or inappropriate -- even physicians admit that -- but, of course, it is other physicians doing all that. No one likes to believe it is their doctor, and few doctors will admit that they are the problem.

Dunning-Kruger, indeed.

Much as they'd like us to, it is not enough for us to always assume that our healthcare professionals and institutions are qualified, much less "the best." It is not enough for us to trust that their opinions are enough to base our care recommendations on. It is not enough to believe that local practice patterns are right for our care, even when they are at variance with national norms or best practices.

"Trust" is seen as essential to the patient-physician relationship, the supposed cornerstone of our healthcare system, but trust needs to be earned. We need facts. We need data. We need empirically-validated care. We need accountability.

Otherwise, we just fall victim to healthcare's Dunning-Kruger effect.

---

”Is the US Healthcare System Suffering from the Dunning-Kruger Effect?" was authored by Kim Bellard and first published in his blog, From a Different Perspective.... It is reprinted by Open Health News with permission from the author. The original post can be found here.

- Tags:

- beginner's bubble of overconfidence

- best doctors

- best hospitals

- Brian Resnic

- cognitive bias

- confident idiots

- David Dunning

- Dunning-Kruger effect

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

- Justin Kruger

- Kim Bellard

- medical licensing system

- Michael Frakes

- Olga Khazan

- Pacific Standard

- US healthcare system

- Vox

- Login to post comments